Bitcoin took the world by surprise in the year 2009 and popularized the idea of decentralized secure monetary transactions. The concepts behind it, however, can be extended to much more than just digital currencies. Ethereum attempts to do that, marrying the power of decentralized transactions with a Turing-complete contract system. Read on as we explore how it works!

"Ethereum marries the power of decentralized transactions with Turing-complete contracts!"

Tweet This

This is part 1 of a 3 post series.

Introduction: Bitcoin and the Double-Spending Problem

In 2009, someone, under the alias of Satoshi Nakamoto, released this iconic Bitcoin whitepaper. Bitcoin was poised to solve a very specific problem: how can the double-spending problem be solved without a central authority acting as arbiter to each transaction?

To be fair, this problem had been in the minds of researchers for some time before Bitcoin was released. But where previous solutions were of research quality, Bitcoin succeeded in bringing a working, production ready design to the masses.

The earliest references to some of the concepts directly applied to Bitcoin are from the 1990s. In 2005, Nick Szabo, a computer scientist, introduced the concept of Bitgold, a precursor to Bitcoin, sharing many of its concepts. The similarities between Bitgold and Bitcoin are sufficient that some people have speculated he might be Satoshi Nakamoto.

The double-spending problem is a specific case of transaction processing. Transactions, by definition, must either happen or not. Additionally, some (but not all) transactions must provide the guarantee of happening before or after other transactions (in other words, they must be atomic). Atomicity gives rise to the notion of ordering: transactions either happen or not before or after other transactions. A lack of atomicity is precisely the problem of the double-spending problem: "spending", or sending money from spender A to receiver B, must happen at a specific point in time, and before and after any other transactions. If this were not the case, it would be possible to spend money more than once in separate but simultaneous transactions.

When it comes to everyday monetary operations, transactions are usually arbitrated by banks. When a user logs-in to his or her home banking system and performs a wire transfer, it is the bank that makes sure any past and future operations are consistent. Although the process might seem simple to outsiders, it is actually quite an involved process with clearing procedures and settlement requirements. In fact, some of these procedures consider the chance of a double-spending situation and what to do in those cases. It should not come as a surprise that these quite involved processes, resulting in considerable but seemingly impossible to surmount delays, where the target of computer science researchers.

The Blockchain

So, the main problem any transactional system appliead to finance must address is "how to order transactions when there is no central authority". Furthermore, there can be no doubts as to whether the sequence of past transactions is valid. For a monetary system to succeed, there can be no way any parties can modify previous transactions. In other words, a "vetting process" for past transactions must also be in place. This is precisely what the blockchain system in Bitcoin was designed to address.

If you are interested in reading about systems that must reach consensus and the problems they face, the paper for The Byzantine Generals Problem is a good start.

Although at this point the concept of what a blockchain is is murky, before getting into details about it, let's go over the problems the blockchain attempts to address.

Validating Transactions

Public-key cryptography is a great tool to deal with one of the problems: validating transactions. Public-key cryptography relies on the asymmetrical mathematical complexity of a very specific set of problems. The asymmetry in public-key cryptography is embodied in the existance of two keys: a public and a private key. These keys are used in tandem for specific purposes. In particular:

- Data encrypted with the public-key can only be decrypted by using the private-key.

- Data signed with the private-key can be verified using the public-key.

The private-key cannot be derived from the public-key, but the public-key can be derived from the private-key. The public-key is meant to be safely shared and can usually be freely exposed to anyone.

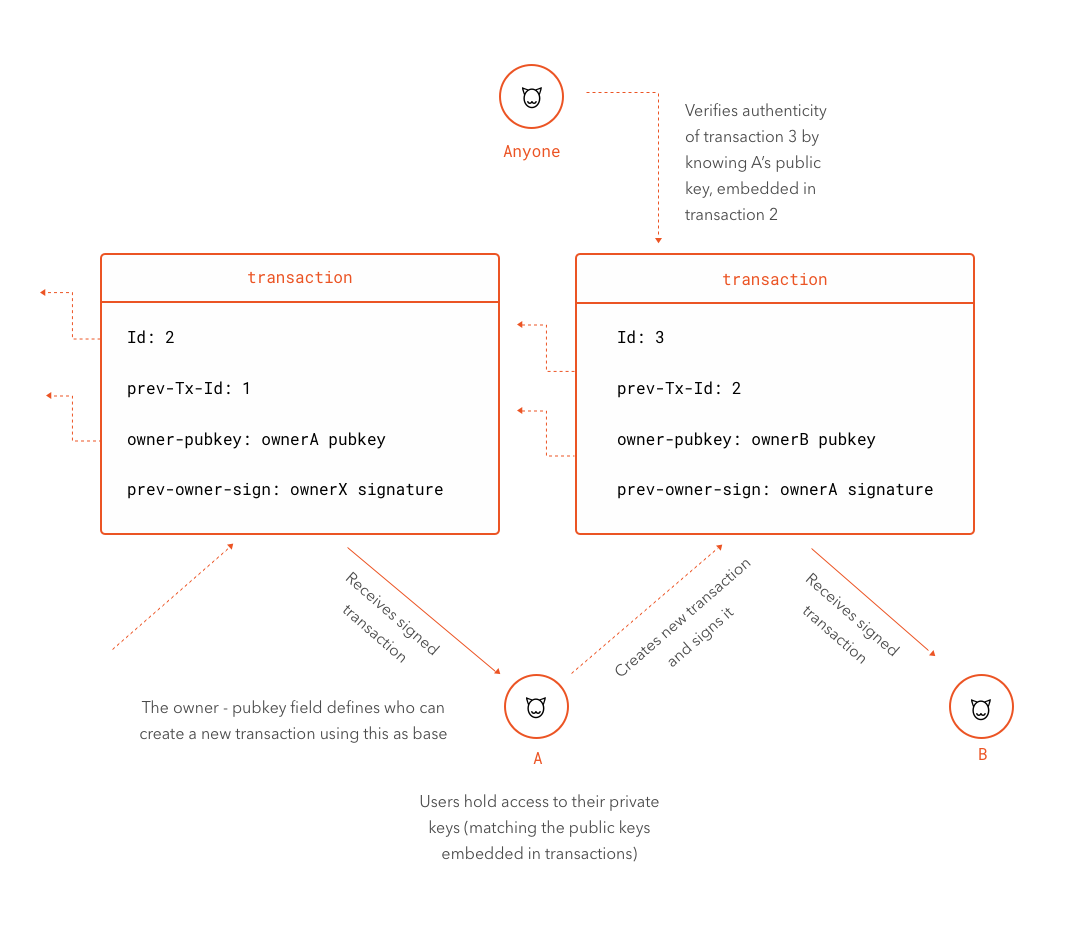

Of interest for creating a verifiable set of transactions is the operation of signing data. Let's see how a very simple transaction can be verified through the use of public-key cryptography.

Let's say there is an account holder A who owns 50 coins. These coins weere sent to him as part of a previous transaction. Account holder A now wants to send these coins to account holder B. B, and anybody else who wants to scrutinize this transaction, must be able to verify that it was actually A who sent the coins to B. Furthermore, they must be able to see B redeemed them, and noone else. Obviously, they should also be able to find the exact point in time, relative to other transactions, in which this transaction took place. However, at this point we cannot do this. We can, fortunately, do everything else.

For our simple example, let's say the data in the transaction is just an identifier for the previous transaction (the one that gave A 50 coins in first place), the public-key of the current owner and the signature from the previous owner (confirming he or she sent those coins to A in first place):

{

"previous-transaction-id": "FEDCBA987654321...",

"owner-pubkey": "123456789ABCDEF...",

"prev-owner-signature": "AABBCCDDEEFF112233..."

}The number of coins of the current transaction is superfluous: it is simply the same amount as the previous transaction linked in it.

Proof that A is the owner of these coins is already there: his or her public-key is embedded in the transaction. Now whatever action is taken by A must be verified in some way. One way to do this would be to add information to the transaction and then produce a new signature. Since A wants to send money to B, the added information could simply be B's public-key. After creating this new transaction it could be signed using A's private-key. This proves A, and only A, was involved in the creating of this transaction. In other words, in JavaScript based pseudo-code:

function aToB(privateKeyA, previousTransaction, publicKeyB) {

const transaction = {

"previous-transaction-id": hash(previousTransaction),

"owner-pubkey": publicKeyB

};

transaction["prev-owner-signature"] = sign(privateKeyA, transaction);

return transaction;

}An interesting thing to note is that we have defined transactions IDs as simply the hash of their binary representation. In other words, a transaction ID is simply its hash (using an, at this point, unspecified hashing algorithm). This is convenient for several reasons we will explain later on. For now, it is just one possible way of doing things.

Let's take the code apart and write it down step-by-step:

- A new transaction is constructed pointing to the previous transaction (the one that holds A's 50 coins) and including B's public signature (new transaction = old transaction ID plus receiver's public key).

- A signature is produced using the new transaction and the previous transaction owner's private key (A's private key).

That's it. The signature in the new transaction creates a verifiable link between the new transaction and the old one. The new transaction points to the old one explicitly and the new transaction's signature can only be generated by the holder of the private-key of the old transaction (the old transaction explicitly tells us who this is through the owner-pubkey field). So the old transaction holds the public-key of the one who can spend it, and the new transaction holds the public-key of the one who received it, along with the signature created with the spender's private-key.

If this seems hard to grasp at this point, think of it this way: it is all derived from this simple expression: data signed with the private-key can be verified using the public-key. There is nothing more to it. The spender simply signs data that says "I am the owner of transaction ID XXX, I hereby send every coin in it to B". B, and anybody else, can check that it was A, and only A, who wrote that. To do so, they need only access to A's public-key, which is available in the transaction itself. It is mathematically guaranteed that no key other than A's private-key can be used in tandem with A's public-key. So by simply having access to A's public-key anyone can see it was A who sent money to B. This makes B the rightful owner of that money. Of course, this is a simplification. There are two things we have not considered: who said those 50 coins where of A's property (or, in other words, did A just take ownership of some random transaction, is he or she the rightful owner?) and when exactly did A send the coins to B (was it before or after other transactions?).

If you are interested in learning more about the math behind public-key cryptography, a simple introduction with code samples is available in chapter 7 of The JWT Handbook.

Before getting into the matter of ordering, let's first tackle the problem of coin genesis. We assumed A was the rightful owner of the 50 coins in our example because the transaction that gave A his or her coins was simply modeled like any other transaction: it had A's public-key in the owner field, and it did point to a previous transaction. So, who gave those coins to A? What's more, who gave the coins to that other person? We need only follow the transaction links. Each transaction points to the previous one in the chain, so where did those 50 coins come from? At some point that chain must end.

To understand how this works, it is best to consider an actual case, so let's see how Bitcoin handles it. Coins in Bitcoin were and are created in two different ways. First there is the unique genesis block. The genesis block is a special, hardcoded transaction that points to no other previous transaction. It is the first transaction in the system, has a specific amount of Bitcoins, and points to a public-key that belongs to Bitcoin creator Satoshi Nakamoto. Some of the coins in this transaction were sent to some addresses, but they never were really used that much. Most of the coins in Bitcoin come from another place: they are an incentive. As we will see in the next section about ordering transactions, the scheme employed to do this requires nodes in the network to contribute work in the form of computations. To create an incentive for more nodes to contribute computations, a certain amount of coins are awarded to contributing nodes when they successfully complete a task. This incentive essentially results in special transactions that give birth to new coins. These transactions are also ends to links of transactions, as well as the genesis block. Each coin in Bitcoin can be traced to either one of these incentives or the genesis block. Many cryptocurrency systems adopt this model of coin genesis, each with its own nuances and requirements for coin creation. In Bitcoin, per design, as more coins get created, less coins are awarded as incentive. Eventually, coin creation will cease.

Ordering Transactions

The biggest contribution Bitcoin brought to existing cryptocurrency schemes was a decentralized way to make transactions atomic. Before Bitcoin, researchers proposed different schemes to achieve this. One of those schemes was a simple voting system. To better understand the magic of Bitcoin's approach, it is better to explore these attempts.

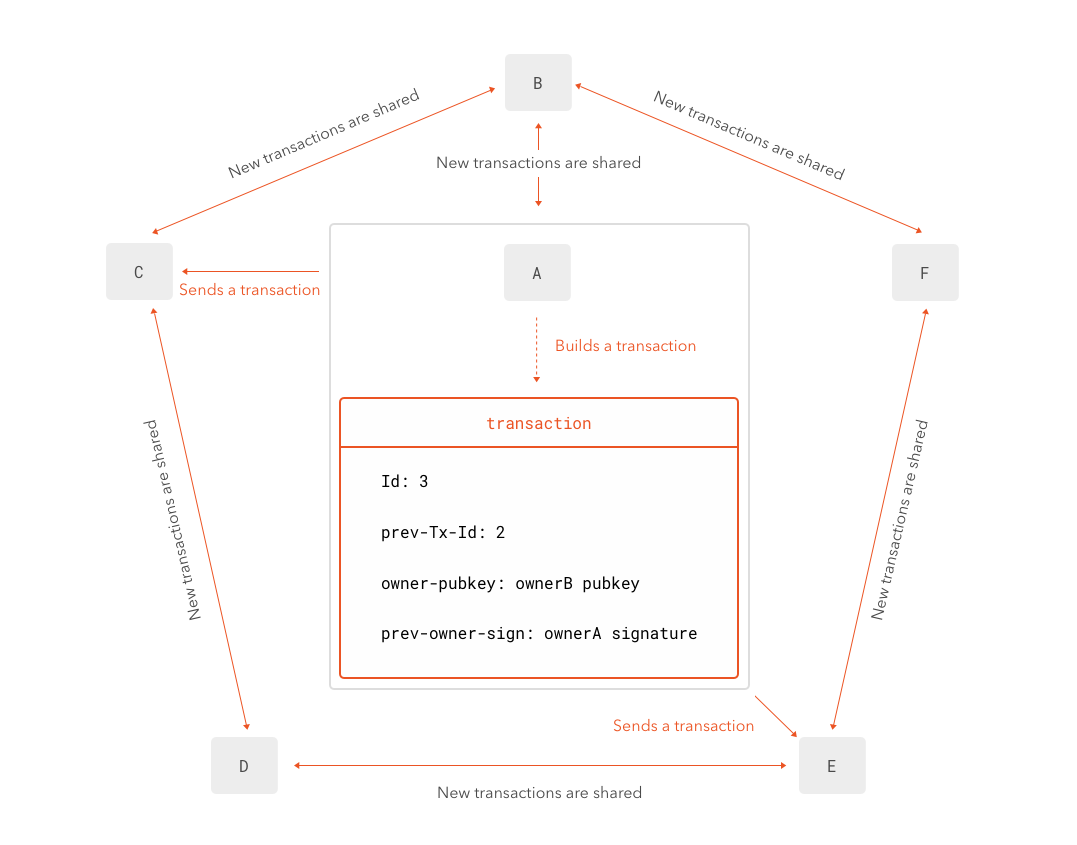

In a voting system, each transaction gets broadcast by the node performing it. So, to continue with the example of A sending 50 coins to B, A prepares a new transaction pointing to the one that gave him or her those 50 coins, then puts B's public-key in it and uses his or her own private-key (A's) to sign it. This transaction is then sent to each node known by A in the network. Let's say that in addition to A and B, there are three other nodes: C, D, E.

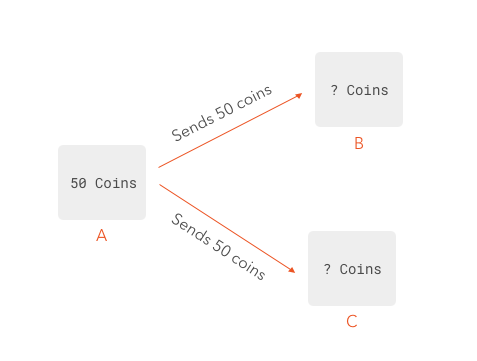

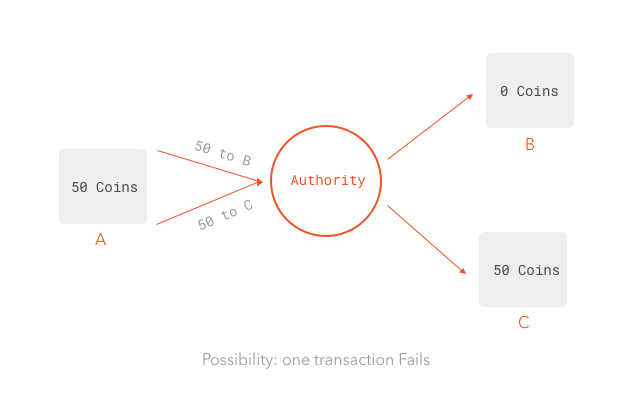

Now let's imagine A is in fact a malicious node. Although it appears A wants to send B 50 coins, at the same time A broadcasts this transaction, it also broadcasts a different one: A sends those same 50 coins to C.

const aToB = {

"previous-transaction-id": "FEDCBA987654321...",

"owner-pubkey": "123456789ABCDEF...", // B

"prev-owner-signature": "..."

};

const aToC = {

"previous-transaction-id": "FEDCBA987654321...",

"owner-pubkey": "00112233445566...", // C

"prev-owner-signature": "..."

};Note how previous-transaction-id points to the same transaction. A sends simultaneously this transaction to different nodes in the network. Who gets the 50 coins? Worse, if those 50 coins were sent in exchange for something, A might get goods from B and C although one of them won't get the coins.

Since this is a distributed network, each node should have some weight in the decision. Let's consider the voting system mentioned before. Each node should now cast a vote on whether to pick which transaction goes first.

| Node | Vote |

|---|---|

| A | A to B |

| B | A to B |

| C | A to C |

| D | A to C |

| E | A to B |

Each node casts a vote and A to B gets picked as the transaction that should go first. Obviously, this invalidates the A to C transaction that points to the same coins as A to B. It would appear this solution works, but only superficially so. Let's see why.

First, let's consider the case A has colluded with some other node. Did E cast a random vote or was it in some way motivated by A to pick one transaction over the other? There is no real way to determine this.

Secondly, our model does not consider the speed of propagation of transactions. In a sufficiently large network of nodes, some nodes may see some transactions before others. This causes votes to be unbalanced. It is not possible to determine whether a future transaction might invalidate the ones that have arrived. Even more, it is not possible to determine whether the transaction that just arrived was made before or after some other transaction waiting for a vote. Unless transactions are seen by all nodes, votes can be unfair. Worse, some node could actively delay the propagation of a transaction.

Lastly, a malicious node could inject invalid transactions to cause a targeted denial of service. This could be used to favor certain transactions over others.

Votes do not fix these problems because they are inherent to the design of the system. Whatever is used to favor one transaction over the other cannot be left to choice. As long as a single node, or group of nodes, can, in some way, favor some transactions over others, the system cannot work. It is precisely this element that made the design of cryptocurrencies such a hard endeavor. A stroke of genius was needed to overcome such a profound design issue.

The problem of malicious nodes casting a vote in distributed systems is best known as The Byzantine Generals Problem. Although there is mathematical proof that this problem can be overcome as long as there is a certain ratio of non-malicious nodes, this does not solve the problem for cryptocurrencies: nodes are cheap to add. Therefore, a different solution is necessary.

Physics to the Rescue

Whatever system is used to ensure some transactions are preferred over others, no node should be able to choose which of these are with 100% certainty. And there is only one way one can be sure this is the case: if it is a physical impossibility for the node to be able to do this. Nodes are cheap to add, so no matter how many nodes a malicious user controls, it should still be hard for him or her to use this to his or her advantage.

The answer is CPU power. What if ordering transactions required a certain amount of work, verifiable work, in such a way that it would be hard to perform initially, but cheap to verify. In a sense, cryptography works under the same principles: certain related operations are computationally infeasible to perform while others are cheap. Encrypting data is cheap next to brute-forcing the encryption key. Deriving the public-key from the private-key is cheap, while it is infeasible to do it the other way around. Hashing data is cheap, while finding a hash with a specific set of requirements (by modifying the input data) is not. And that is the main operation Bitcoin and other cryptocurrencies rely on to make sure no node can get ahead of others, on average. Let's see how this works.

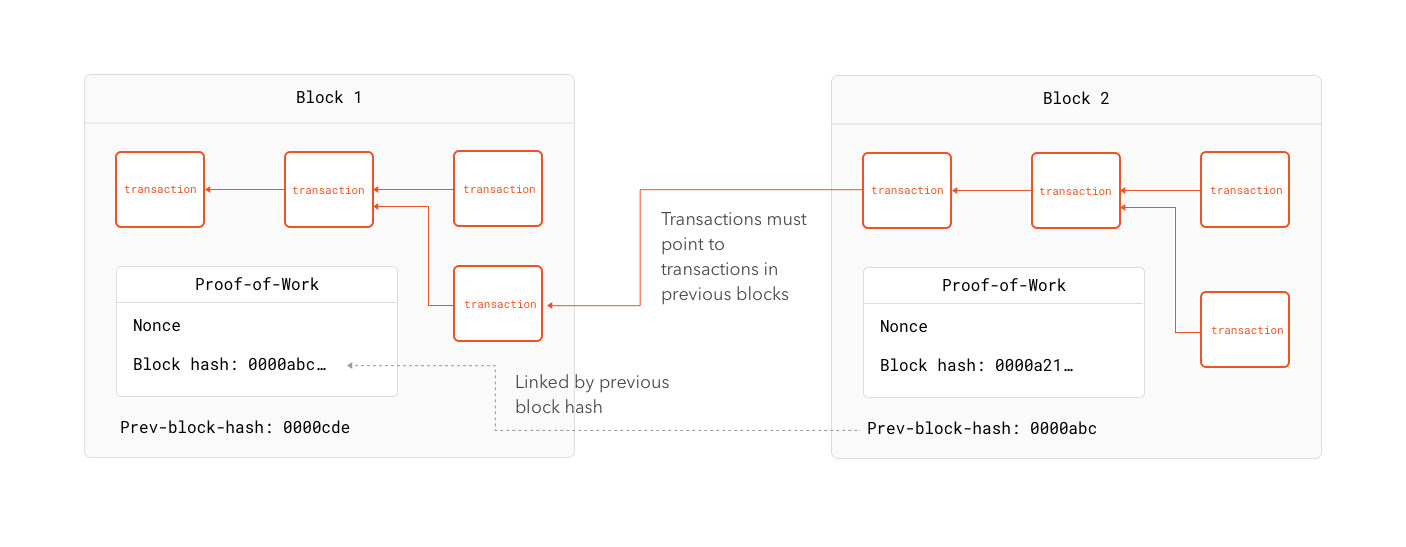

First, let's define what a block is. A block is simply a group of transactions. Inside the block, these transactions are set in a specific order and fulfill the basic requirements of any transaction. In particular, an invalid transaction (such as one taking funds from an account with no funds) cannot be part of a block. In addition to the transactions, a block carries something called proof-of-work. The proof-of-work is data the allows any node to verify that the one who created this block performed a considerable amount of computational work. In other words, no node can create a valid block without performing an indefinite but considerable amount of work. We will see how this works later, but for now know that creating any block requires a certain amount of computing power and that any other node can check that that power has been spent by whomever created the block.

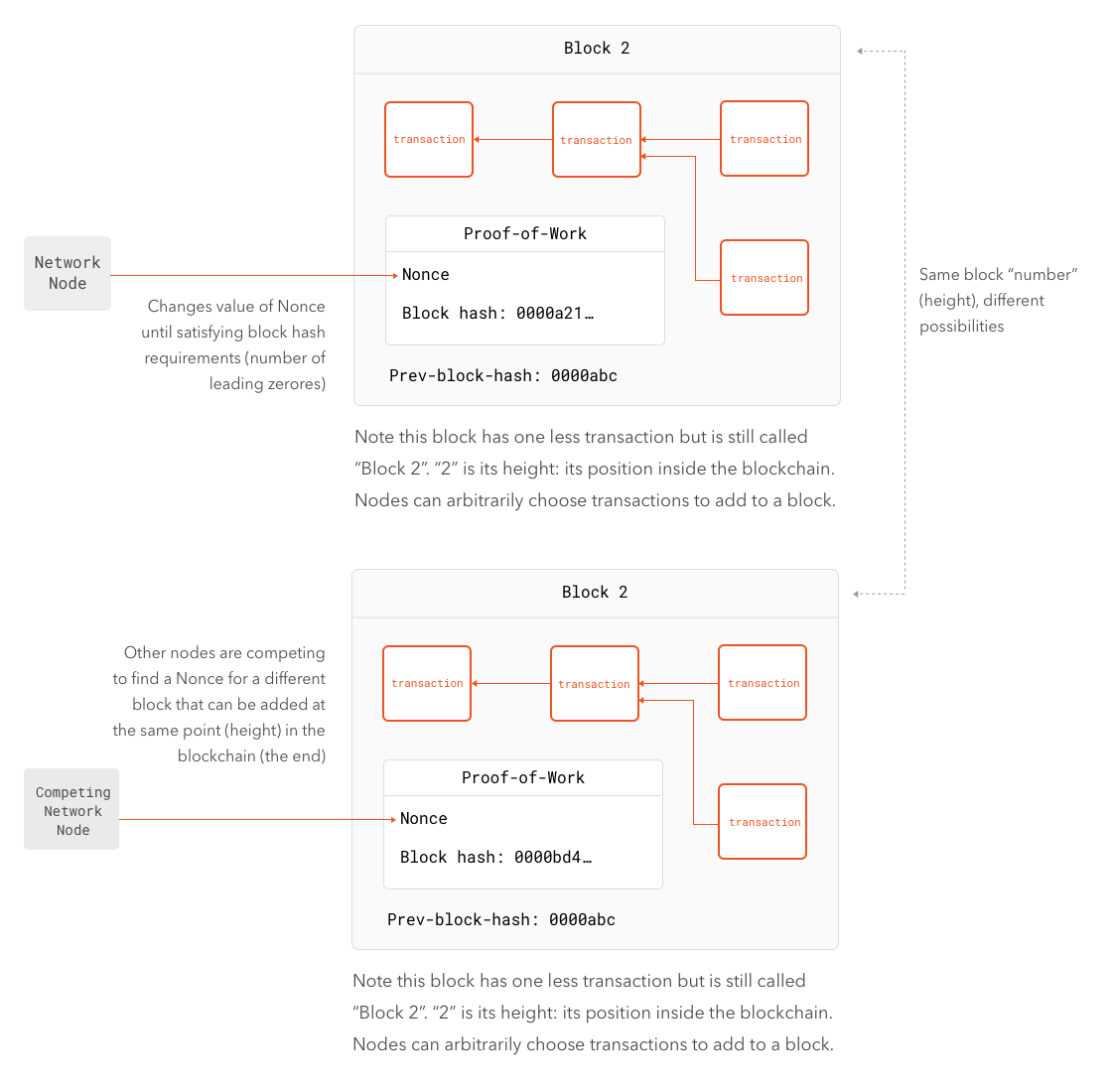

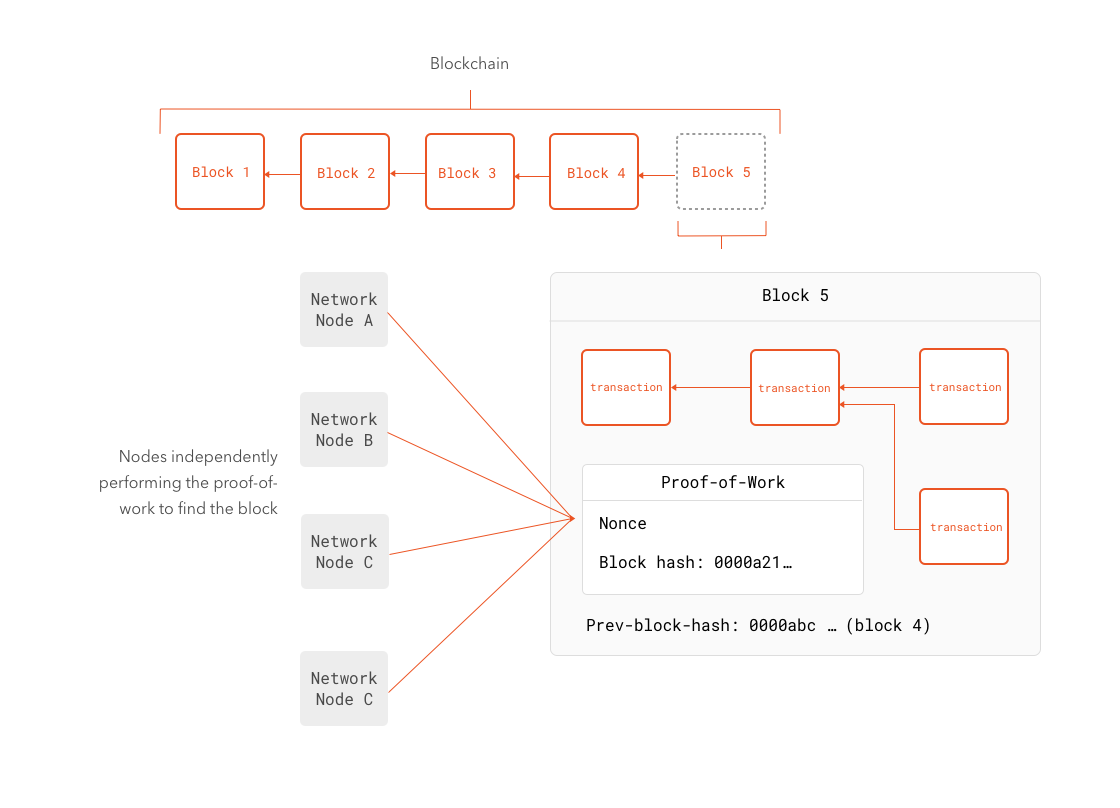

Now let's go back to our previous example of a malicious node, A, double-spending 50 coins by trying to create to two separate transactions at the same time, one sending money to B and the other to C. After A broadcasts both transactions to the network, every node working on creating blocks (which may include A) pick a number of transactions and order them in whichever way they prefer. These nodes will note that two incompatible transactions are part of the same block and will discard one. They are free to pick which one to discard. After placing these transactions in the order they chose, each node starts solving the puzzle of finding a hash for the block that fits the conditions set by the protocol. One simple condition could be "find a hash for this block with three leading zeroes". To iterate over possible solutions for this problem, the block contains a special variable field known as the "nonce". Each node must iterate as many times as necessary until they find the nonce that creates a block with a hash that fits the conditions set by the protocol (three leading zeroes). Since each change in the nonce basically results in a random output for a cryptographically secure hash function, finding the nonce is a game of chance and can only be sped up by increasing computation power. Even then, a less powerful node might find the right nonce before a more powerful node, due to the randomness of the problem.

This creates an interesting scenario because even if A is a malicious node and controls another node (for instance, E) any other node on the network still has a chance of finding a different valid block. In other words, this scheme makes it hard for malicious nodes to take control of the network.

Still, the case of a big number of malicious nodes colluding and sharing CPU power must be considered. In fact, an entity controlling a majority of the nodes (in terms of CPU power, not number) could exercise a double-spending attack by creating blocks faster than other nodes. Big enough networks rely on the difficulty of amassing CPU power. While in a voting system an attacker need only add nodes to the network (which is easy, as free access to the network is a design target), in a CPU power based scheme an attacker faces a physical limitation: getting access to more and more powerful hardware.

Definition

At last we can attempt a full definition of what a blockchain is and how it works. A blockchain is a verifiable transaction database carrying an ordered list of all transactions that ever occurred. Transactions are stored in blocks. Block creation is a purposely computationally intensive task. The difficulty of creation of a valid block forces anyone to spend a certain amount of work. This ensures malicious users in a big enough network cannot easily outpass honest users. Each block in the network points to the previous block, effectively creating a chain. The longer a block has been in the blockchain (the farther it is from the last block), the lesser the probability it can ever be removed from it. In other words, the older the block, the more secure it is.

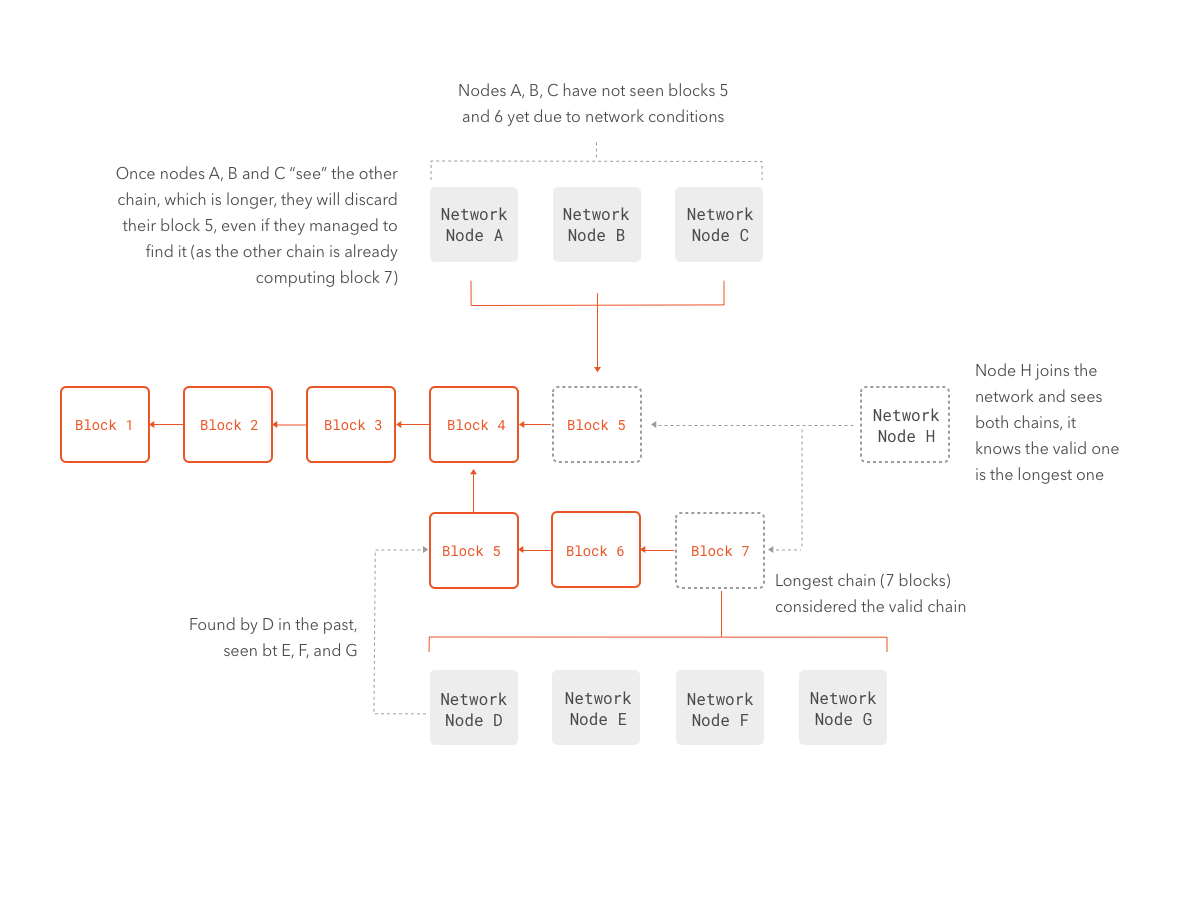

One important detail we left in previous paragraphs is what happens when two different nodes find different but still valid blocks at the same time. In a sense, this looks like the same problem transactions had: which one to pick. In contrast with transactions, the proof-of-work system required for each block lets us find a convenient solution: since each block requires a certain amount of work, it is only natural that the only valid blockchain is the one with most blocks in it. Think about it: if the proof-of-work system works because each block demands a certain amount of work (and time), the longest set of valid blocks is the hardest to break. If a malicious node or group of nodes were to attempt to create a different set of valid blocks, by always picking the longest blockchain, they would always have to redo a bigger number of blocks (because each node points to the previous one, changing one block forces a change in all blocks after it). This is also the reason malicious groups of nodes need to control over 50% of the computational power of the network to actually carry any attack. Less than that, and the rest of the network will create a longer blockchain faster.

Valid blocks that are valid but find their way into shorter forks of the blockchain are discarded if a longer version of the blockchain is computed by other nodes. The transactions in the discarded blocks are sent again to the pool of transactions awaiting inclusion into future blocks. This causes new transactions to remain in an uncofirmed state until they find their way into the longest possible blockchain. Nodes periodically receive newer versions of the blockchain from other nodes.

It is entirely possible for the network to be forked if a sufficiently large number of nodes gets disconnected at the same time from another part of the network. If this happens, each fork will continue creating blocks in isolation from the other. If the networks merge again in the future, the nodes will compare the different versions of the blockchains and pick the longer one. The fork with the greater computational power will always win. If the fork were to be sustained for a long enough period of time, a big number of transactions would be undone when the merge took place. It is for this reason that forks are problematic.

Forks can also be caused by a change in the protocol or the software running the nodes. These changes can result in nodes invalidating blocks that are considered valid by other nodes. The effect is identical to a network-related fork.

Aside: a Perpetual Message System Using Webtasks and Bitcoin

Although we have not delved into the specifics of how Bitcoin or Ethereum handle transactions, there is a certain programmability built into them. Bitcoin allows for certain conditions to be specified in each transaction. If these conditions are met, the transaction can be spent. Ethereum, on the other hand, goes much further: a Turing-complete programming language is built into the system. We will focus on Ethereum in the next post in this series, but for now we will take a look at creative ways in which the concepts of the blockchain can be exploited for more than just sending money. For this, we will develop a simple perpetual message system on top of Bitcoin. How will it work?

We have seen the blockchain stores transactions that can be verified. Each transaction is signed by the one who can perform it and then broadcast to the network. It is then stored inside a block after performing a proof-of-work. This means that any information embedded in the transaction is stored forever inside the blockchain. The timestamp of the block serves as proof of the message's date, and the proof-of-work process serves as proof of its immutable nature.

Bitcoin uses a scripting system that describes steps a user must perform to spend money. The most common script is simply "prove you are the owner of a certain private-key by signing this message with it". This is known as the "pay to pubkey hash" script. In decompiled form it looks like:

<sig> <pubKey> OP_DUP OP_HASH160 <pubKeyHash> OP_EQUALVERIFY OP_CHECKSIGWhere <sig> and <pubKey> are provided by the spender and the rest is specified by the original sender of the money. This is simply a sequence of mixed data and operations. The interpreter for this script is a stack-based virtual machine. The details of execution are out of scope for this article, but you can find a nice summary at the Bitcoin Wiki. The important take from this is that transactions can have data embedded in them in the scripts.

In fact, there exists a valid opcode for embedding data inside a transaction: the OP_RETURN opcode. Whatever data follows the OP_RETURN opcode is stored in the transaction. Of course, there is a limit for the amount of data allowed: 40-bytes. This is very little, but still certain interesting applications can be performed with such a tiny amount of storage. One of them is our perpetual message system. Another interesting use case is the "proof of existence" concept. By storing a hash of an asset in the blockchain, it serves as proof of its existence at the point it was added to a block. In fact, there already exists such a project. There is nothing preventing you from using our perpetual message system for a similar use. Yet other uses allow the system to prepare transactions that can only be spent after conditions are met, or when the spender provides proof of having a certain digital asset, of when a certain minimum number of users agree to spend it. Programmability opens up many possibilities and makes for yet another great benefit of cryptocurrencies in contrast with traditional monetary systems.

The Implementation

Our system will work as an HTTP service. Data will we passed in JSON format as the body of POST requests. The service will have three endpoints plus one for debugging.

The /new endpoint

It creates a new user using the username and password passed in. Sample body:

{

"id": "username:password", // password is not hashed for simplicity,

// TLS is required!

"testnet": true // True to use Bitcoin's test network

}The response is of the form:

{

"address": "..." // A Bitcoin address for the user just created

}The /address endpoint

Returns the address for an existing user. Sample body:

{

"id": "username:password", // password is not hashed for simplicity,

// TLS is required!

}The response is identical to the /new endpoint.

The /message endpoint

Broadcasts a transaction to the Bitcoin network with the message stored in it. A fee is usually required for the network to accept the transaction (though some nodes may accept transactions with no fees). Messages can be at most 33 bytes long. Sample body:

{

"id": "username:password",

"fee": 667,

"message": "test"

}The response is either a transaction id or an error message. Sample of a successful response:

{

"status": "Message sent!",

"transactionId": "3818b4f03fbbf091d5b52edd0a58ee1f1834967693f5029e5112d36f5fdbf2f3"

}Using the transaction id one can see the message stored in it. One can use any publicly available blockchain explorer to do this.

The /debugNew endpoint

Similar to the /new endpoint but allows one to create an user with an existing Bitcoin private key (and address). Sample body:

{

"id": "username:password", // password is not hashed for simplicity,

// TLS is required!

"testnet": true, // True to use Bitcoin's test network

"privateKeyWIF": "..." // A private key in WIF format.

// Note testnet keys are different from livenet keys,

// so the private key must agree with the

// value of the "testnet" key in this object

}The response is identical to the /new endpoint.

The Code

The most interesting endpoint is the one that builds and broadcasts the transaction (/message). We use the bitcore-lib and bitcore-explorers libraries to do this:

getUnspentUtxos(from).then(utxos => {

let inputTotal = 0;

utxos.some(utxo => {

inputTotal += parseInt(utxo.satoshis);

return inputTotal >= req.body.fee;

});

if(inputTotal < req.body.fee) {

res.status(402).send('Not enough balance in account for fee');

return;

}

const dummyPrivateKey = new bitcore.PrivateKey();

const dummyAddress = dummyPrivateKey.toAddress();

const transaction =

bitcore.Transaction()

.from(utxos)

.to(dummyAddress, 0)

.fee(req.body.fee)

.change(from)

.addData(`${messagePrefix}${req.body.message}`)

.sign(req.account.privateKeyWIF);

broadcast(transaction.uncheckedSerialize()).then(body => {

if(req.webtaskContext.secrets.debug) {

res.json({

status: 'Message sent!',

transactionId: body,

transaction: transaction.toString(),

dummyPrivateKeyWIF: dummyPrivateKey.toWIF()

});

} else {

res.json({

status: 'Message sent!',

transactionId: body

});

}

}, error => {

res.status(500).send(error.toString());

});

}, error => {

res.status(500).send(error.toString());

});The code is fairly simple:

- Gets the unspent transactions for an address (i.e. the coins available, the balance).

- Build a new transaction using the unspent transactions as input.

- Point the transaction to a new, empty address. Assign 0 coins to that address (do not send money unnecessarily).

- Set the fee.

- Set the address where the unspent money will get sent back (the change address).

- Add our message.

- Broadcast the transaction.

Bitcoin requires transactions to be constructed using the money from previous transactions. That is, when coins are sent, it is not the origin address that is specified, rather it is the transactions pointing to that address that are included in a new transaction that points to a different destination address. From these transactions is subtracted the money that is then sent to the destination. In our case, we use these transactions to pay for the fee. Everything else gets sent back to our address.

Deploying the Example

Thanks to the power of Webtasks, deploying and using this code is a piece of cake. First clone the repository:

git clone git@github.com:auth0-blog/ethereum-series-bitcoin-perpetual-message-example.gitNow make sure you have the Webtask command-line tools installed:

npm install -g wt-cliIf you haven't done so, initialize your Webtask credentials (this is a one time process):

wt initNow deploy the project:

cd ethereum-series-bitcoin-perpetual-message-example

wt create --name bitcoin-perpetual-message --meta 'wt-node-dependencies={"bcryptjs":"2.4.3","bitcore-lib":"0.13.19","bitcore-explorers-bitcore-lib-0.13.19":"1.0.1-3"}' app.jsYour project is now ready to test! Use CURL to try it out:

curl -X POST https://wt-sebastian_peyrott-auth0_com-0.run.webtask.io/bitcoin-perpetual-message/new -d '{ "id":"test:test", "testnet":true }' -H "Content-Type: application/json"

{"address":"mopYghMw5i7rYiq5pfdrqFt4GvBus8G3no"} # This is your Bitcoin addressYou now have to add some funds to your new Bitcoin address. If you are on Bitcoin's testnet, you can simply use a faucet.

Faucets are Bitcoin websites that give free coins to addresses. These are easy to get for the testnet. For the "livenet" you need to buy Bitcoins using a Bitcoin exchange.

Now send a message!

curl -X POST https://wt-sebastian_peyrott-auth0_com-0.run.webtask.io/bitcoin-perpetual-message/message -d '{ "id":"test:test", "fee":667, "message":"test" }' -H "Content-Type: application/json"

{"status":"Message sent!","transactionId":"3818b4f03fbbf091d5b52edd0a58ee1f1834967693f5029e5112d36f5fdbf2f3"}Now you can look at the transaction using a blockchain explorer and the transaction id. If you go down to the bottom of the page in the link before you will see our message with a prefix WTMSG: test. This will get stored in the blockchain forever.

Try it yourself! The webtask at https://wt-sebastian_peyrott-auth0_com-0.run.webtask.io/bitcoin-perpetual-message/ is live. You will need to create your own account and fund it, though.

You can also get the full code for this example and run it!

Conclusion

Blockchains enable distributed, verified transactions. At the same time they provide a creative solution to the double-spending problem. This has enabled the rise of cryptcurrencies, of which Bitcoin is the most popular example. Millions of dollars in Bitcoins are traded each day, and the trend is not giving any signs of slowing down. Bitcoin provides a limited set of operations to customize transactions. Still, many creative applications have appeared through the combination of blockchains and computations. Ethereum is the greatest example of these: marrying decentralized transactions with a Turing-complete execution environment. In the next post in the series we will take a closer look at how Ethereum differs from Bitcoin and how the concept of decentralized applications was brought to life by it.