Troy Hunt recently published a blog post titled “Authentication guidance for the modern era”. It has a big pile of solid advice on what password rules your website should use, with references to formal government recommendations, always useful for convincing colleagues or a boss.

One of the projects I worked on during my time at Google was their unified account system (specifically, anti-hijacking). Login systems are a part of most websites, so reading Troy’s article inspired me to put together some advice for building them.

1. Ideally, Don’t

Whatever your business is, user authentication is not your core competency. Modern login systems are expected to do a lot. Passwords are only the start. If you are successful you will eventually also want:

- Forgotten password recovery

- Email address verification

- Log out, which is harder than it looks (see below)

- Password brute-forcing protection

- Two-factor authentication via SMS, phone app and hardware key

- Account hijacking protection (when an attacker already knows the correct password, and the user does not have 2FA)

- Region/language/name/profile photo preferences

- Support for mobile/desktop sign-in

- Unusual activity notifications

- Phone-only sign-in

As big companies raise user expectations and attackers get better, the effort to keep up is becoming impractical. Fortunately, you can outsource your authentication to those companies using OAuth.

Often web developers see adding a “sign in with Facebook” or “sign in with Google” button as a kind of optional nice-to-have, which comes only after building their own account system. If you’re reading this because you’re starting a new website from scratch, I argue that “Sign in with …” should be the only option you offer. Building your own account system these days is like building your own datacenters instead of using AWS. It’s an expensive distraction.

Sometimes people worry that if they only offer “Sign in with …” the big ID providers might one day try to steal their customers. The usual indication someone’s worrying about this is you sign in with an ID provider and are then asked to set a password anyway. Don’t worry about this. In the unlikely event that this happens, you can always migrate your customer base to a new system of your own later by simply emailing them a link.

2. Use Email/Phone Numbers to Identify Users

Don’t ask users to pick usernames, even if you want a username-oriented experience like on a chat forum. Users are always identified to you by email address, phone number, or both, and if you want a different name for user-to-user identification (a display name), that should be chosen separately. Why?

- You will ask for the email address anyway.

- If the username becomes a form of self-expression on your service, users will want to change it from time to time.

- Users forget usernames but not their email/phone numbers.

- Picking a username is frustrating. Every time a user selects a name that’s already taken, some will give up, and your customer acquisition pipeline narrows.

- Separating username from display name will reduce the temptation to impose arbitrary restrictions on how users appear, like forbidding spaces.

3. Don’t Use Passwords at All

If you aren’t quite ready to rely 100% on third party ID providers, at least do everyone a favor and don’t make users pick a password at all.

This isn’t as stupid as it sounds. You are already asking the user for their email address. The very first feature you will add to your login system after going live is forgotten password recovery, which will work by sending the user a clickable link via an email. Therefore anyone who can read your user’s email can log in as them anyway, and your own site password adds no extra security.

Instead, skip the first step and go straight to the second, your login system can be as simple as emailing the user a link that sets a login cookie when clicked. Medium.com is an example of a site that does this.

This approach works as long as every device where the user might log in to your service has an email client. This is true for desktops, laptops, phones, and tablets. It is not true for game consoles or TVs, but you probably aren’t targeting them yet. If you are, it’s better to use a Bluetooth style pairing process anyway, as these devices don’t have convenient keyboards.

There have been suggestions in the past that users can be confused by the lack of a password entry box. But the modern Google sign-in experience starts by asking the user for their email address only, so it’s unlikely users are confused by this any more … and the benefits are huge.

This approach has an additional benefit: some users have phone numbers but not email addresses. This is especially true in developing countries, so if this is a possible target market for your website, you may eventually want to support users who can only log in by receiving a code to their phone. Such accounts won’t have passwords at all, so if you assumed all users do have passwords, it would require you to go back and add lots of special cases to security-sensitive code paths (this can easily lead to fatal mistakes).

4. Don’t Use Secret Questions

If you simply must use passwords, perhaps you don’t want to try explaining to your boss why you did things differently. At the very least, don’t let the user recover using secret questions and answers.

- The answers to secret questions are often trivially guessed. Users find it incredibly hard to think of questions that only they could answer and nobody else.

- Pre-supplied questions make the guessing problem worse.

- Pre-supplied questions often have a cultural bias that makes them useless for many users (e.g., “what was your high school’s mascot?”)

- Some savvy users realize they can’t think of a hard-to-guess answer, so just use it as a second password field, meaning they then can’t recover when they forget.

- There is a long list of high profile celebrity and VIP hacks that worked by abusing password recovery flows. You don’t want this to be you.

Google had severe problems with secret questions. A couple of my old colleagues published research on it that’s worth reading or watching.

Some examples of problematic Q/As:

- Q: Favourite food. A: Pizza. The answer is always pizza. You can break into around 20% of English-speaking accounts with just a single guess using this answer. With just ten guesses, you can break into over a third of all English-speaking accounts that have this question. For Korean accounts, you can get into 43% of all accounts within ten guesses.

- Q: On what day did I get married? A: Thursday. A custom question, but fatally flawed — the attacker needed only five guesses, too few to be detected as a brute-forcing attempt.

- Q: In which city was I born? A: Seoul. In some countries, almost everyone lives in a handful of large cities. Observing the language, the ID verification UI is written in can thus narrow down the list of possible cities dramatically. For Korean accounts, you only need ten guesses to break 40% of accounts using this question.

- Q: What was the name of my first teacher? A: Mr. Smith, Smith, John, John S. Smith, JOHN SMITH, Jon Smth. All of these answers are correct but won’t be matched by a straightforward implementation. I added fuzzy matching for questions like these because users so often got them ‘nearly’ right. The matching logic often needs to understand something about the question (Levenshtein distance by itself is insufficient for things like street addresses). Good luck doing this for all the languages your product supports!

Not surprisingly, professional account systems do not use knowledge of secret Q/A alone to allow users to recover accounts. It’s just one signal, amongst many. I give you a <2% chance of writing something sophisticated enough to get this right. That’s why Google phased secret Q/A out in favor of SMS recovery. SMS based recovery has its own issues, but it’s still a lot better than secret questions.

5. Outsource 2-Factor Authentication

Two-factor auth is a pretty common feature these days. Again, doing this well is hard, expensive, and you do not want to implement it yourself.

SMS is unreliable, especially in some countries. Recovery codes will occasionally just not show up. You will eventually want to implement phone calls with speech synthesis as a result because phone calls are much more reliable, but now you need multi-lingual speech synthesis engines.

Doing lots of SMSs or phone calls is extremely expensive, even if you can negotiate good bulk discounts.

People lose access to their phone numbers all the time. If you rely on email addresses, your password recovery flow can be pretty easy, but once solid 2FA is introduced, your password recovery becomes the weakest point in the system. If you don’t upgrade it, attackers will simply go around it. If you block it, then you will discover that …

2FA can be abused by attackers who add it to accounts they phished or hacked. This is to prevent real users from stealing the account back whilst the malicious activity is performed.

Phone numbers are vulnerable to porting attacks, so the trend is towards asking users to set up mobile apps or security keys. Implementing those is even more work, and of course, both of those can be lost too, so you will ultimately still need some customer support flow to help them recover.

As you’re figuring out, 2FA adds a lot of manual customer support work because you can no longer just push users towards email or secret Q/A based recovery. That’s expensive.

Some of these problems are fundamental, but most of them are solved already by the big players who will pay the phone bills and customer support people on your behalf, for free! Still, if you don’t want to use them, there are startups that will solve small parts of the 2FA puzzle for you.

6. Don’t Force Password Changes

Troy already covered this just fine, so I won’t repeat it here, except to say that this is really important. Don’t require users to change passwords just because it’s been a while.

- Some users won’t make it through the process, and you will bleed users.

- Some users will be smarter than you and use tricks like changing their password (once, twice, three times) and then immediately changing it back to their old password, meaning you will end up wanting to store a history of recent passwords to prevent this behavior. But I bet your first implementation won’t do this.

- It doesn’t improve security anyway.

7. Don’t Expire Sessions

Yet another best practice that isn’t. It’s tempting to set your session cookies to expire. Sometimes people think that this improves security for the same reason they think expiring people’s passwords improves security.

- Attackers tend to perform malicious activities immediately, so expirations don’t help much.

- Session expiry trains users that random unexpected password prompts are normal, which makes them incredibly easy to phish.

- Sessions that expire randomly create an explosion of bugs that your developers will waste large amounts of time on. Most parts of your website will not be written to handle the case of sessions expiring halfway through an action, so you’ll have to go back and fix them, assuming you even notice the problems at all. Expiry tends to surface as user reports of random flakiness, which are hard to track down.

8. Remember Sign-Out

Getting sign-out wrong is remarkably common in immature account systems. It sounds superficially easy, but the most obvious ways to do it have flaws.

- Simply deleting the session cookie is fine as a convenience to the user, but means you can’t recover from XSS. Once an XSS is found, you may wish to invalidate possibly stolen session cookies, but if sign-out is just “ask the browser to delete the cookie,” then you can’t do it.

- Adding timestamps to session cookies and then setting a “last sign-out time” requires every action to check against the accounts database to discover if the user’s session is too old. This can slow things down, meaning developers will be tempted to optimize it out (it doesn’t seem dangerous to do so after all). But then if they remove the check for an endpoint of interest to attackers, you’ve still got the problem in step one. Additionally, this means signing out of one browser or device signs the user out of all of them, which isn’t expected behavior.

The right way to do this is by keeping a list of invalidated session cookies with in-memory caching. But for most companies, there’s a less costly approach which is good enough: have the user’s sign-out link be just a way to clear the session cookie and nothing more, then make session cookies expire but be automatically and silently replaced every 5 minutes or so. The act of replacing an expired session cookie consults the database to see if the administrators have forced a logout. If the user is presenting an expired cookie, then they are required to log in again. This recognizes that cleaning up after cookies may have been stolen is a relatively rare event.

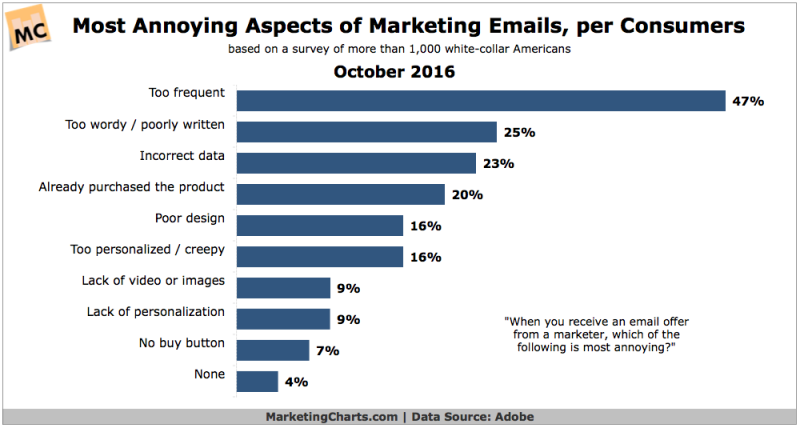

9. Separate Account Emails from Marketing Mail

The obvious way to send password recovery links, signup verifications, etc. is simply from your company’s main email server. Unfortunately, some people in your company are trying to build a “relationship” with the user by sending them commercial mails they don’t want.

Even if users agreed to receive these during account signup, many of them don’t want them anymore, and some will solve this by reporting them as spam. This is an expedient solution for the savvy user who has noticed that simply clicking “Report spam” a couple of times makes the emails go away, without any mental effort expended on finding tiny light-grey-on-white-6pt-font unsubscribe links or … gasp … writing email filters.

Unfortunately, this entirely normal behavior will start to degrade the reputation of your main email domain. Mail from your account system may start going into the user’s spam folder. We’ve all seen warnings on signup or password recovery flows telling us to check our spam folders, that’s why.

One way to solve this is by buying a separate top-level domain to send your account mails from and making sure to configure DKIM. But then some users will notice the mismatch and report your email as phishing instead. The best solution is to send your marketing emails from a different DKIM domain, but that will likely involve picking a fight with your product folks. Still … the moment you chose to roll your own, you accepted this pain, remember?

10. Keep Your Password Database Well Protected

If you have passwords, you have a database attackers want (and frequently get). They don’t care about your company directly; they just want the passwords so they can try them at higher value targets. Yet data breaches are embarrassing and can lead to big penalties even if the direct impact on your customers is low. A database of OAuth tokens is of far less value to attackers, and thus you’re much less likely to be attacked.

Aside: Securing Applications with Auth0

Are you building a B2C, B2B, or B2E tool? Auth0, can help you focus on what matters the most to you, the special features of your product. Auth0 can improve your product's security with state-of-the-art features like passwordless, breached password surveillance, and multifactor authentication.

We offer a generous free tier so you can get started with modern authentication.

Conclusion

There is far more I could write about account systems. Defending your site against malicious account hacking/signup is an entire book all by itself. I can’t write that book, but you can watch this video of a talk I gave in 2012 instead if you’re curious.

But it’s fair to say the task is deceptively large. That’s why I keep recommending you bite the bullet and outsource your account management to the big boys. Writing design documents for “log out” is not your core business. Diagnosing why you’re bleeding users who forgot their password is not your core business. Diagnosing why SMS message delivery to Peru isn’t reliable isn’t your core business. Every dollar you spend on these things is a dollar your competitors who use “Sign in with …” are spending on their core business.

So throw out your password database, and don’t look back.