As JavaScript development gets more and more common, namespaces and depedencies get much more difficult to handle. Different solutions were developed to deal with this problem in the form of module systems. In this post we will explore the different solutions currently employed by developers and the problems they try to solve. Read on!

Introduction: Why Are JavaScript Modules Needed?

If you are familiar with other development platforms, you probably have some notion of the concepts of encapsulation and dependency. Different pieces of software are usually developed in isolation until some requirement needs to be satisfied by a previously existing piece of software. At the moment that other piece of software is brought into the project a dependency is created between it and the new piece of code. Since these pieces of software need to work together, it is of importance that no conflicts arise between them. This may sound trivial, but without some sort of encapsulation it is a matter of time before two modules conflict with each other. This is one of the reasons elements in C libraries usually carry a prefix:

#ifndef MYLIB_INIT_H

#define MYLIB_INIT_H

enum mylib_init_code {

mylib_init_code_success,

mylib_init_code_error

};

enum mylib_init_code mylib_init(void);

// (...)

#endif //MYLIB_INIT_HEncapsulation is essential to prevent conflicts and ease development.

When it comes to dependencies, in traditional client-side JavaScript development, they are implicit. In other words, it is the job of the developer to make sure dependencies are satisfied at the point any block of code is executed. Developers also need to make sure dependencies are satisfied in the right order (a requirement of certain libraries).

The following example is part of Backbone.js's examples. Scripts are manually loaded in the correct order:

<!DOCTYPE html>

<html lang="en">

<head>

<meta charset="utf-8">

<title>Backbone.js Todos</title>

<link rel="stylesheet" href="todos.css"/>

</head>

<body>

<script src="../../test/vendor/json2.js"></script>

<script src="../../test/vendor/jquery.js"></script>

<script src="../../test/vendor/underscore.js"></script>

<script src="../../backbone.js"></script>

<script src="../backbone.localStorage.js"></script>

<script src="todos.js"></script>

</body>

<!-- (...) -->

</html>As JavaScript development gets more and more complex, dependency management can get cumbersome. Refactoring is also impaired: where should newer dependencies be put to maintain proper order of the load chain?

JavaScript module systems attempt to deal with these problems and others. They were born out of necessity to accommodate the ever growing JavaScript landscape. Let's see what the different solutions bring to the table.

An Ad-Hoc Solution: The Revealing Module Pattern

Most module systems are relatively recent. Before they were available, a particular programming pattern started getting used in more and more JavaScript code: the revealing module pattern.

var myRevealingModule = (function () {

var privateVar = "Ben Cherry",

publicVar = "Hey there!";

function privateFunction() {

console.log( "Name:" + privateVar );

}

function publicSetName( strName ) {

privateVar = strName;

}

function publicGetName() {

privateFunction();

}

// Reveal public pointers to

// private functions and properties

return {

setName: publicSetName,

greeting: publicVar,

getName: publicGetName

};

})();

myRevealingModule.setName( "Paul Kinlan" );This example was taken from Addy Osmani's JavaScript Design Patterns book.

JavaScript scopes (at least up to the appearance of let in ES2015) work at the function level. In other words, whatever binding is declared inside a function cannot escape its scope. It is for this reason the revealing module pattern relies on functions to encapsulate private contents (as many other JavaScript patterns).

In the example above, public symbols are exposed in the returned dictionary. All other declarations are protected by the function scope enclosing them. It is not necessary to use var and an immediate call to the function enclosing the private scope; a named function can be used for modules as well.

This pattern has been in use for quite some time in JavaScript projects and deals fairly nicely with the encapsulation matter. It does not do much about the dependencies issue. Proper module systems attempt to deal with this problem as well. Another limitation lies in the fact that including other modules cannot be done in the same source (unless using eval).

Pros

- Simple enough to be implemented anywhere (no libraries, no language support required).

- Multiple modules can be defined in a single file.

Cons

- No way to programmatically import modules (except by using

eval). - Dependencies need to be handled manually.

- Asynchronous loading of modules is not possible.

- Circular dependencies can be troublesome.

- Hard to analyze for static code analyzers.

CommonJS

CommonJS is a project that aims to define a series of specifications to help in the development of server-side JavaScript applications. One of the areas the CommonJS team attempts to address are modules. Node.js developers originally intended to follow the CommonJS specification but later decided against it. When it comes to modules, Node.js's implementation is very influenced by it:

// In circle.js

const PI = Math.PI;

exports.area = (r) => PI * r * r;

exports.circumference = (r) => 2 * PI * r;

// In some file

const circle = require('./circle.js');

console.log( `The area of a circle of radius 4 is ${circle.area(4)}`);One evening at Joyent, when I mentioned being a bit frustrated some ludicrous request for a feature that I knew to be a terrible idea, he said to me, "Forget CommonJS. It's dead. We are server side JavaScript." - NPM creator Isaac Z. Schlueter quoting Node.js creator Ryan Dahl

There are abstractions on top of Node.js's module system in the form of libraries that bridge the gap between Node.js's modules and CommonJS. For the purposes of this post, we will only show the basic features which are mostly the same.

In both Node's and CommonJS's modules there are essentially two elements to interact with the module system: require and exports. require is a function that can be used to import symbols from another module to the current scope. The parameter passed to require is the id of the module. In Node's implementation, it is the name of the module inside the node_modules directory (or, if it is not inside that directory, the path to it). exports is a special object: anything put in it will get exported as a public element. Names for fields are preserved. A peculiar difference between Node and CommonJS arises in the form of the module.exports object. In Node, module.exports is the real special object that gets exported, while exports is just a variable that gets bound by default to module.exports. CommonJS, on the other hand, has no module.exports object. The practical implication is that in Node it is not possible to export a fully pre-constructed object without going through module.exports:

// This won't work, replacing exports entirely breaks the binding to

// modules.exports.

exports = (width) => {

return {

area: () => width * width

};

}

// This works as expected.

module.exports = (width) => {

return {

area: () => width * width

};

}CommonJS modules were designed with server development in mind. Naturally, the API is synchronous. In other words, modules are loaded at the moment and in the order they are required inside a source file.

"CommonJS modules were designed with server development in mind."

Tweet This

Pros

- Simple: a developer can grasp the concept without looking at the docs.

- Dependency management is integrated: modules require other modules and get loaded in the needed order.

requirecan be called anywhere: modules can be loaded programmatically.- Circular dependencies are supported.

Cons

- Synchronous API makes it not suitable for certain uses (client-side).

- One file per module.

- Browsers require a loader library or transpiling.

- No constructor function for modules (Node supports this though).

- Hard to analyze for static code analyzers.

Implementations

We have already talked about one implementation (in partial form): Node.js.

For the client there are currently two popular options: webpack and browserify. Browserify was explicitly developed to parse Node-like module definitions (many Node packages work out-of-the-box with it!) and bundle your code plus the code from those modules in a single file that carries all dependencies. Webpack on the other hand was developed to handle creating complex pipelines of source transformations before publishing. This includes bundling together CommonJS modules.

Asynchronous Module Definition (AMD)

AMD was born out of a group of developers that were displeased with the direction adopted by CommonJS. In fact, AMD was split from CommonJS early in its development. The main difference between AMD and CommonJS lies in its support for asynchronous module loading.

"The main difference between AMD and CommonJS lies in its support for asynchronous module loading."

Tweet This

//Calling define with a dependency array and a factory function

define(['dep1', 'dep2'], function (dep1, dep2) {

//Define the module value by returning a value.

return function () {};

});

// Or:

define(function (require) {

var dep1 = require('dep1'),

dep2 = require('dep2');

return function () {};

});Asynchronous loading is made possible by using JavaScript's traditional closure idiom: a function is called when the requested modules are finished loading. Module definitions and importing a module is carried by the same function: when a module is defined its dependencies are made explicit. An AMD loader can therefore have a complete picture of the dependency graph for a given project at runtime. Libraries that do not depend on each other for loading can thus be loaded at the same time. This is particularly important for browsers, where startup times are essential to a good user experience.

Pros

- Asynchronous loading (better startup times).

- Circular dependencies are supported.

- Compatibility for

requireandexports. - Dependency management fully integrated.

- Modules can be split in multiple files if necessary.

- Constructor functions are supported.

- Plugin support (custom loading steps).

Cons

- Slightly more complex syntactically.

- Loader libraries are required unless transpiled.

- Hard to analyze for static code analyzers.

Implementations

Currently the most popular implementations of AMD are require.js and Dojo.

Using require.js is pretty straightforward: include the library in your HTML file and use the data-main attribute to tell require.js which module should be loaded first. Dojo has a similar setup.

ES2015 Modules

Fortunately, the ECMA team behind the standardization of JavaScript decided to tackle the issue of modules. The result can be seen in the latest release of the JavaScript standard: ECMAScript 2015 (previously known as ECMAScript 6). The result is syntactically pleasing and compatible with both synchronous and asynchronous modes of operation.

//------ lib.js ------

export const sqrt = Math.sqrt;

export function square(x) {

return x * x;

}

export function diag(x, y) {

return sqrt(square(x) + square(y));

}

//------ main.js ------

import { square, diag } from 'lib';

console.log(square(11)); // 121

console.log(diag(4, 3)); // 5Example taken from Axel Rauschmayer blog

The import directive can be used to bring modules into the namespace. This directive, in contrast with require and define is not dynamic (i.e. it cannot be called at any place). The export directive, on the other hand, can be used to explicitly make elements public.

The static nature of the import and export directive allows static analyzers to build a full tree of dependencies without running code. ES2015 does not support dynamic loading of modules, but a draft specification does:

System.import('some_module')

.then(some_module => {

// Use some_module

})

.catch(error => {

// ...

});In truth, ES2015 only specifies the syntax for static module loaders. In practice, ES2015 implementations are not required to do anything after parsing these directives. Module loaders such as System.js are still required. A draft specification for browser module loading is available.

This solution, by virtue of being integrated in the language, lets runtimes pick the best loading strategy for modules. In other words, when asynchronous loading gives benefits, it can be used by the runtime.

Update (Feb 2017): there is a now a specification for dynamic loading of modules. This is a proposal for future releases of the ECMAScript standard.

Pros

- Synchronous and asynchronous loading supported.

- Syntactically simple.

- Support for static analysis tools.

- Integrated in the language (eventually supported everywhere, no need for libraries).

- Circular dependencies supported.

Cons

- Still not supported everywhere.

Implementations

Unfortunately none of the major JavaScript runtimes support ES2015 modules in their current stable branches. This means no support in Firefox, Chrome or Node.js. Fortunately many transpilers do support modules and a polyfill is also available. Currently, the ES2015 preset for Babel can handle modules with no trouble.

The All-in-One Solution: System.js

You may find yourself trying to move away from legacy code using one module system. Or you may want to make sure whatever happens, the solution you picked will still work. Enter System.js: a universal module loader that supports CommonJS, AMD and ES2015 modules. It can work in tandem with transpilers such as Babel or Traceur and can support Node and IE8+ environments. Using it is a matter of loading System.js in your code and then pointing it to your base URL:

<script src="system.js"></script>

<script>

// set our baseURL reference path

System.config({

baseURL: '/app',

// or 'traceur' or 'typescript'

transpiler: 'babel',

// or traceurOptions or typescriptOptions

babelOptions: {

}

});

// loads /app/main.js

System.import('main.js');

</script>As System.js does all the job on-the-fly, using ES2015 modules should generally be left to a transpiler during the build step in production mode. When not in production mode, System.js can call the transpiler for you, providing seamless transition between production and debugging environments.

Aside: Auth0 Authentication with JavaScript

At Auth0, we make heavy use of full-stack JavaScript to help our customers to manage user identities, including password resets, creating, provisioning, blocking, and deleting users. Therefore, it must come as no surprise that using our identity management platform on JavaScript web apps is a piece of cake.

Auth0 offers a free tier to get started with modern authentication. Check it out, or sign up for a free Auth0 account here!

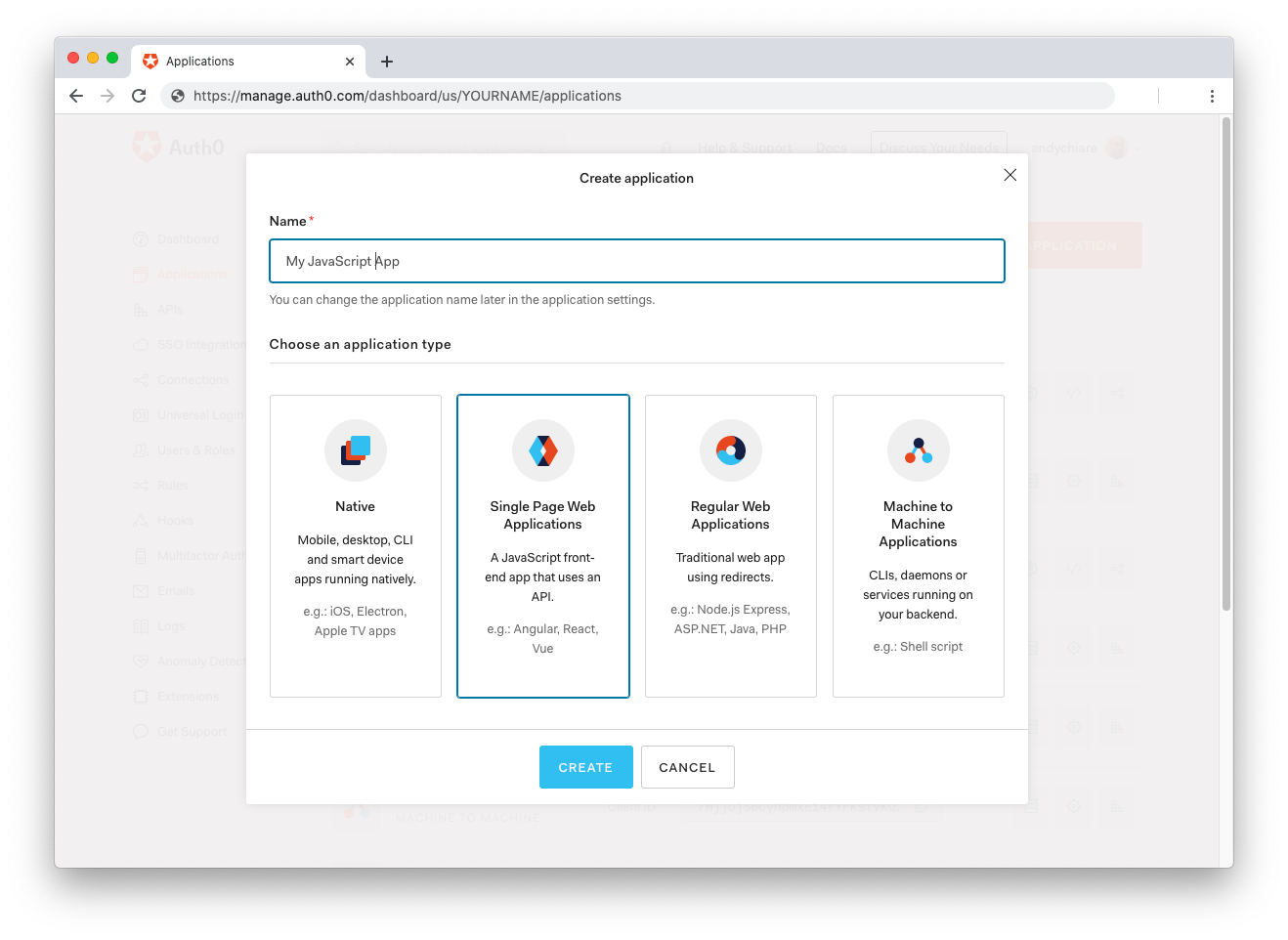

Then, go to the Applications section of the Auth0 Dashboard and click on "Create Application". On the dialog shown, set the name of your application and select Single Page Web Applications as the application type:

After the application has been created, click on "Settings" and take note of the domain and client id assigned to your application. In addition, set the Allowed Callback URLs and Allowed Logout URLs fields to the URL of the page that will handle login and logout responses from Auth0. In the current example, the URL of the page that will contain the code you are going to write (e.g. http://localhost:8080).

Now, in your JavaScript project, install the auth0-spa-js library like so:

npm install @auth0/auth0-spa-jsThen, implement the following in your JavaScript app:

import createAuth0Client from '@auth0/auth0-spa-js';

let auth0Client;

async function createClient() {

return await createAuth0Client({

domain: 'YOUR_DOMAIN',

client_id: 'YOUR_CLIENT_ID',

});

}

async function login() {

await auth0Client.loginWithRedirect();

}

function logout() {

auth0Client.logout();

}

async function handleRedirectCallback() {

const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated();

if (!isAuthenticated) {

const query = window.location.search;

if (query.includes('code=') && query.includes('state=')) {

await auth0Client.handleRedirectCallback();

window.history.replaceState({}, document.title, '/');

}

}

await updateUI();

}

async function updateUI() {

const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated();

const btnLogin = document.getElementById('btn-login');

const btnLogout = document.getElementById('btn-logout');

btnLogin.addEventListener('click', login);

btnLogout.addEventListener('click', logout);

btnLogin.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'none' : 'block';

btnLogout.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'block' : 'none';

if (isAuthenticated) {

const username = document.getElementById('username');

const user = await auth0Client.getUser();

username.innerText = user.name;

}

}

window.addEventListener('load', async () => {

auth0Client = await createClient();

await handleRedirectCallback();

});Replace the

YOUR_DOMAINandYOUR_CLIENT_IDplaceholders with the actual values for the domain and client id you found in your Auth0 Dashboard.

Then, create your UI with the following markup:

<p>Welcome <span id="username"></span></p>

<button type="submit" id="btn-login">Sign In</button>

<button type="submit" id="btn-logout" style="display:none;">Sign Out</button>Your application is ready to authenticate with Auth0!

Check out the Auth0 SPA SDK documentation to learn more about authentication and authorization with JavaScript and Auth0.

Conclusion

Building modules and handling dependencies was cumbersome in the past. Newer solutions, in the form of libraries or ES2015 modules, have taken most of the pain away. If you are looking at starting a new module or project, ES2015 is the right way to go. It will always be supported and current support using transpilers and polyfills is excellent. On the other hand, if you prefer to stick to plain ES5 code, the usual split between AMD for the client and CommonJS/Node for the server remains the usual choice. Don't forget to leave us your thoughts in the comments section below. Hack on!