New exciting features are coming for JavaScript!

Even if the final approval of the new ECMAScript 2020 (ES2020) language specification will be in June, you can start to take a look and try them right now!

Follow me in this article to explore what's new.

Dealing with Modules

Some important innovations concern modules. Among these, a feature that developers have been requesting for a long time is the dynamic import. But let's go in order and see them in detail.

Dynamic imports

The current mechanism for importing modules is based on static declarations like the following:

import * as MyModule from "./my-module.js";This statement has a couple of constraints:

- all the code of the imported module is evaluated at the load time of the current module

- the specifier of the module (

"./my-module.js"in the example above) is a string constant, and you can not change it at runtime

These constraints prevent loading modules conditionally or on-demand. Also, evaluating each dependent module at load time affects the performance of the application.

The new import() statement solves these issues by allowing you to import modules dynamically. The statement accepts a module specifier as an argument and returns a promise. Also, the module specifier can be any expression returning a string. This is great news because we can now load JavaScript modules at runtime as in the following example:

const baseModulePath = "./modules";

const btnBooks = document.getElementById("btnBooks");

let bookList = [];

btnBooks.addEventListener("click", async e => {

const bookModule = await import(`${baseModulePath}/books.js`);

bookList = bookModule.loadList();

});This code shows how to load the books.js module right when the user clicks the btnBooks button. After loading the module, the click event handler will use the loadList() function exported by the module. Note how the module to import is specified through a string interpolation.

"The long-awaited dynamic import is now available in JavaScript ES2020."

Tweet This

Import meta data

The import.meta object provides metadata for the current module. The JavaScript engine creates it, and its current available property is url. This property's value is the URL from which the module was loaded, including any query parameter or hash.

As an example, you could use the import.meta.url property to build the URL of a data.json file stored in the same folder of the current module. The following code gets this result:

const dataUrl = new URL("data.json", import.meta.url);In this case, the import.meta.url provides the URL class with the base URL for the data.json file.

New export syntax

The import statement introduced by the ECMAScript 2015 specifications provides you with many forms of modules importing. The following are a few examples:

import {value} from "./my-module.js";

import * from "./my-module.js";In some cases, you may need to export objects imported from another module. A handy export syntax may help you, as shown in the following:

export {value} from "./my-module.js";

export * from "./my-module.js";This symmetry between import and export statements is convenient from a developer experience standpoint. However, a specific case wasn't supported before these new specifications:

import * as MyModule from "./my-module.js";To export the MyModule namespace, you should use two statements:

import * as MyModule from "./my-module.js";

export {MyModule};Now, you can get the same result with one statement, as shown below:

export * as MyModule from "./my-module.js";This addition simplifies your code and keeps the symmetry between import and export statements.

Data Types and Objects

The new ES2020 specifications introduce a new data type, a standardized global object, and a few methods that simplify the developer's life. Let's take a look.

BigInt and arbitrary precision integers

As you know, JavaScript has only one data type for numbers: the Number type. This primitive type allows you to represent 64-bit floating-point numbers. Of course, it also represents integers, but the maximum representable value is 2^53, corresponding to the Number.MAX_SAFE_INTEGER constant.

Without going into the internal details of integer representation, there are situations where you may need a higher precision. Consider the following cases:

- interaction with other systems that provide data as 64-bit integers, such as GUIDs, account numbers, or object IDs

- result of complex mathematical calculations requiring more than 64 bits

The workaround for the first case is representing data as strings. Of course, this workaround doesn't work for the second case.

The new BigInt data type aims to solve these issues. You represent a literal BigInt by simply appending the letter n to a number, as shown in this example:

const aBigInteger = 98765432123456789n;You can also use the BigInt() constructor the same way you use the Number() constructor:

const aBigInteger = BigInt("98765432123456789");The typeof operator now returns the "bigint" string when applied to a BigInt value:

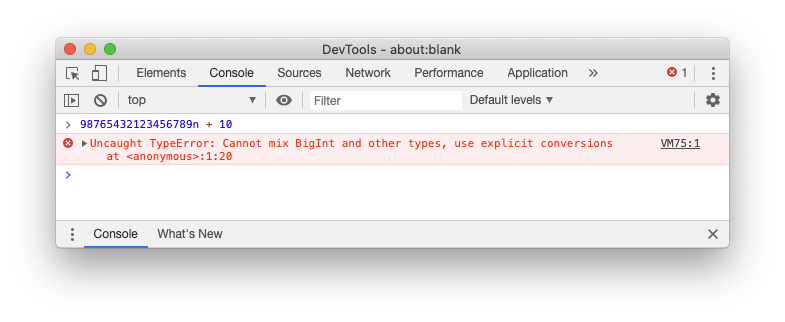

typeof aBigInteger //output: "bigint"Keep in mind that Number and BigInt are different types, so you cannot mix them. For example, the attempt to add a Number value to a BigInt value throws a TypeError exception, as shown by the following picture:

You have to explicitly convert the Number value to a BigInt value by using the BigInt() constructor.

"The BigInt data type is a new 'big' addition to JavaScript."

Tweet This

The matchAll() method for regular expressions

You have several ways to get all matches for a given regular expression. The following is one of these ways, but you can use other approaches:

const regExp = /page (\d+)/g;

const text = 'text page 1 text text page 2';

let matches;

while ((matches = regExp.exec(text)) !== null) {

console.log(matches);

}This code matches all the page x instances within the text variable through iteration. At each iteration, the exec() method runs over the input string, and you obtain a result like the following:

["page 1", "1", index: 5, input: "text page 1 text text page 2", groups: undefined]

["page 2", "2", index: 22, input: "text page 1 text text page 2", groups: undefined]The matchAll() method of String objects allows you to get the same result but in a more compact way and with better performance. The following example rewrites the previous code by using this new method:

const regExp = /page (\d+)/g;

const text = 'text page 1 text text page 2';

let matches = [...text.matchAll(regExp)];

for (const match of matches) {

console.log(match);

}The matchAll() method returns an iterator. The previous example uses the spread operator to collect the result of the iterator in an array.

The globalThis object

Accessing the global object requires different syntaxes, depending on the JavaScript environment. For example, in a browser, the global object is window, but you cannot use it within a Web Worker. In this case, you need to use self. Also, in Node.js the global object is global.

This leads to issues when writing code intended to run in different environments. You might use the this keyword, but it is undefined in modules and in functions running in strict mode.

The globalThis object provides a standard way of accessing the global object across different JavaScript environments. So, now you can write your code in a consistent way, without having to check the current running environment. Remember, however, to minimize the use of global items, since it is considered a bad programming practice.

The Promise.allSettled() method

Currently, JavaScript has two ways to combine promises: Promise.all() and Promise.race().

Both methods take an array of promises as an argument. The following is an example of using Promise.all():

const promises = [fetch("/users"), fetch("/roles")];

const allResults = await Promise.all(promises);Promise.all() returns a promise that is fulfilled when all the promises fulfilled. If at least one promise is rejected, the returned promise is rejected. The rejection reason for the resulting promise is the same as the first rejected promise.

This behavior doesn't provide you with a direct way to get the result of all the promises when at least one of them is rejected. For example, in the code above, if fetch("/users") fails and the corresponding promise rejected, you don't have an easy way to know if the promise of fetch("/roles") is fulfilled or rejected. To have this information, you have to write some additional code.

The new Promise.allSettled() combinator waits for all promises to be settled, regardless of their result. So, the following code lets you know the result of every single promise:

const promises = [fetch("/users"), fetch("/roles")];

const allResults = await Promise.allSettled(promises);

const errors = results

.filter(p => p.status === 'rejected')

.map(p => p.reason);In particular, this code lets you know the reason for the failure of each rejected promise.

New operators

A couple of new operators will make it easier to write and to read your code in very common operations. Guess which ones?

The nullish coalescing operator

How many times you've seen and used expressions like the following?

const size = settings.size || 42;Using the || operator is very common to assign a default value when the one you are attempting to assign is null or undefined. However, this approach could lead to a few potentially unintended results.

For example, the size constant in the example above will be assigned the value 42 also when the value of settings.size is 0. But the default value will also be assigned when the value of settings.size is "" or false.

To overcome these potential issues, now you can use the nullish coalescing operator (??). The previous code becomes as follows:

const size = settings.size ?? 42;This grants that the default value 42 will be assigned to the size constant only if the value of settings.size is null or undefined.

Optional chaining

Consider the following example:

const txtName = document.getElementById("txtName");

const name = txtName ? txtName.value : undefined;You get the textbox with txtName as its identifier from the current HTML document. However, if the HTML element doesn't exist in the document, the txtName constant will be null. So, before accessing its value property, you have to make sure that txtName is not null or undefined.

The optional chaining operator (?.) allows you to have a more compact and readable code, as shown below:

const txtName = document.getElementById("txtName");

const name = txtName?.value;As in the previous example, the name constant will have the the value of txtName.value if txtName is not null or undefined; undefined otherwise.

The benefits of this operator are much more appreciated in complex expressions like the following:

const customerCity = invoice?.customer?.address?.city;You can apply the optional chaining operator also to dynamic properties, as in the following example:

const userName = user?.["name"];In addition, it applies to function or method calls as well:

const fullName = user.getFullName?.();In this case, if the getFullName() method exists, it is executed. Otherwise, the expression returns undefined.

"The nullish coalescing operator and the optional chaining are now a reality in JavaScript."

Tweet This

Using the New Features

Throughout this article, you got an overview of ES2020's new features, and you're probably wondering when you'll be able to use them.

According to caniuse.com, all recent major browsers but Internet Explorer already support the new features brought by ECMAScript 2020. However, at the time of writing, Safari is not supporting the new BigInt data type and the matchAll() method.

The latest version of Node.js supports all the features as well, including dynamic import for enabled ECMAScript modules.

Finally, also the latest versions of the most popular transpilers, like Babel and TypeScript, allow you to use the latest ES2020 features.

Aside: Auth0 Authentication with JavaScript

At Auth0, we make heavy use of full-stack JavaScript to help our customers to manage user identities, including password resets, creating, provisioning, blocking, and deleting users. Therefore, it must come as no surprise that using our identity management platform on JavaScript web apps is a piece of cake.

Auth0 offers a free tier to get started with modern authentication. Check it out, or sign up for a free Auth0 account here!

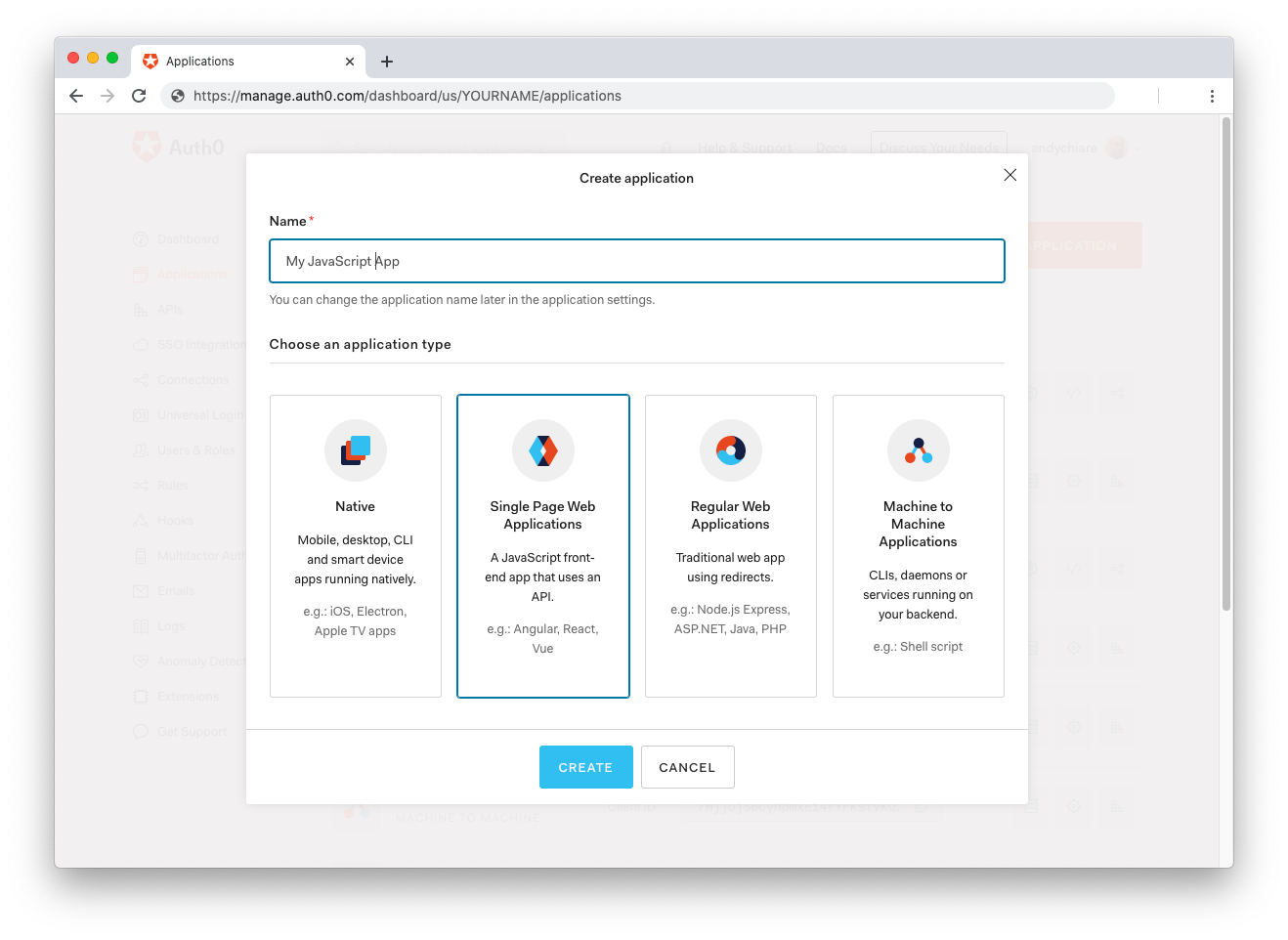

Then, go to the Applications section of the Auth0 Dashboard and click on "Create Application". On the dialog shown, set the name of your application and select Single Page Web Applications as the application type:

After the application has been created, click on "Settings" and take note of the domain and client id assigned to your application. In addition, set the Allowed Callback URLs and Allowed Logout URLs fields to the URL of the page that will handle login and logout responses from Auth0. In the current example, the URL of the page that will contain the code you are going to write (e.g. http://localhost:8080).

Now, in your JavaScript project, install the auth0-spa-js library like so:

npm install @auth0/auth0-spa-jsThen, implement the following in your JavaScript app:

import createAuth0Client from '@auth0/auth0-spa-js';

let auth0Client;

async function createClient() {

return await createAuth0Client({

domain: 'YOUR_DOMAIN',

client_id: 'YOUR_CLIENT_ID',

});

}

async function login() {

await auth0Client.loginWithRedirect();

}

function logout() {

auth0Client.logout();

}

async function handleRedirectCallback() {

const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated();

if (!isAuthenticated) {

const query = window.location.search;

if (query.includes('code=') && query.includes('state=')) {

await auth0Client.handleRedirectCallback();

window.history.replaceState({}, document.title, '/');

}

}

await updateUI();

}

async function updateUI() {

const isAuthenticated = await auth0Client.isAuthenticated();

const btnLogin = document.getElementById('btn-login');

const btnLogout = document.getElementById('btn-logout');

btnLogin.addEventListener('click', login);

btnLogout.addEventListener('click', logout);

btnLogin.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'none' : 'block';

btnLogout.style.display = isAuthenticated ? 'block' : 'none';

if (isAuthenticated) {

const username = document.getElementById('username');

const user = await auth0Client.getUser();

username.innerText = user.name;

}

}

window.addEventListener('load', async () => {

auth0Client = await createClient();

await handleRedirectCallback();

});Replace the

YOUR_DOMAINandYOUR_CLIENT_IDplaceholders with the actual values for the domain and client id you found in your Auth0 Dashboard.

Then, create your UI with the following markup:

<p>Welcome <span id="username"></span></p>

<button type="submit" id="btn-login">Sign In</button>

<button type="submit" id="btn-logout" style="display:none;">Sign Out</button>Your application is ready to authenticate with Auth0!

Check out the Auth0 SPA SDK documentation to learn more about authentication and authorization with JavaScript and Auth0.

Summary

At the end of this quick journey, you learned the new amazing features you can use in JavaScript. Although the final specifications will be approved in June, you do not have to wait. Most popular JavaScript environments are ready. You can use them right now!